Chapter 10: Profit Is Why You Are in Business

Everybody understands that businesses exist to make a profit. Profit is so much a part of how we understand our society that when an organization is set up for any other purpose we explicitly label it a "nonprofit" organization.

Maybe because it sounds greedy, small businesses in particular do not generally talk about profit. Instead they focus on their secondary purposes: to help individuals find the best life insurance at the lowest rates; to provide a worry-free roofing future; to bring the authentic taste of Chicago deep-dish pizza to Podunk, Wisconsin.

Unfortunately, many people get so wrapped up in the secondary purposes of their business that they lose sight of the primary purpose. I was one of them.

Profit Enables You to Pursue Your Other Goals

In the early days of my business, I was consumed with growth and with "the mission." We sell Bible software, so it was not difficult for me to see our work as something nobler than just making a profit. I believed that success meant providing our useful tool for Bible study to as many people in as many countries in as many languages as possible.

Business is about numbers, and I was a true devotee of the numbers. I tracked gross revenue, employee headcount, number of customers, countries served, and languages supported. I made decisions based on growing those numbers. A lower price will sell more units? Let's lower the price. A single customer asked for a Swedish version? Let's build a Swedish version.

It wasn't that I completely ignored profit. I checked in once in a while to see that we still had one. I just didn't worry too much about how big it was, and I did not take the time to find out exactly where it came from. In a high-growth business like ours, I reasoned, we were investing in the future, not trying to make money right now.

Rapid growth, some outside investment, and some very profitable projects held trouble at bay for a few years. But when it caught up with us it hit us hard: on sales of $4.6 million we managed to lose around $900,000. It had been our best year by every other measure. We had higher revenue, sold more units, and employed more people than ever before. We had simply failed to make a profit. In the months that followed, our continued losses threatened our survival. I began to realize that if we did not make profit the focus of our efforts I would have neither the luxury of pursuing our mission nor the convenience of a place to live.

Making a profit is what enables a business to accomplish its mission. Profit needs to be the first priority or you will not have a chance to pursue any others.

Around the time we reached this low point in our business, I attended a meeting of entrepreneurs. Introductions revealed that the man sitting next to me had a locally focused service business a fourth the size of mine. He did not have a quarter-million customers in 140 countries in a dozen languages, and he did not have ambitions to change the world. He did, however, have a consistent profit of 10%. His goals lacked the global scope of mine, but he was actually accomplishing his and making a positive impact locally. For all our size and ambition, the impact I was then most likely to make was an increase in local unemployment.

There Are Lots of Ways to Be Unprofitable

Our huge losses forced us to take a careful look at our business. We discovered that under my careful direction the company had successfully navigated into every major profitability trap:

- We fell in love with our customers. Our customers are some of the nicest people in the world. We sell to pastors, students, and missionaries—people who have chosen giving over earning and who do not have large budgets. We wanted them all to have our software so we kept putting out lower and lower-cost configurations until every potential customer could afford it. We wanted them to love us too, so we spent huge amounts of time doing lots of little things individual customers requested even if they were only of interest to that one customer.

- We valued quantity over quality. We believed that the number of people using our software was the most important metric. We did not distinguish good customers from bad customers, and we would sell at any price to increase the customer count. We put products into cheap "box-o-stuff" collections and offered ridiculous discounts for site licenses and other high-quantity sales.

- We created work to keep the staff busy. When we found ourselves overstaffed (easy to do when you value increasing headcount) we invented new projects just to keep people busy. Without any concern for the size of market we once developed a cuneiform word processor (really!) just to keep some programmers busy for a quarter. Over three years it had a grand total of $350.40 in sales. (This product actually enjoyed a monopoly on the cuneiform word processing market and was successful in terms of winning a large share of its potential users. But even 100% of that market would not have made it a profitable project; all the people in the world writing cuneiform script could meet in my kitchen.

- We took projects at a loss to keep a competitor from getting them. We told ourselves that we wouldn't lose money; we would just have a very small margin. The reality is that we wanted to win the contract so badly that we were willing to deceive ourselves as to our real costs. "It's strategic," we told ourselves.

The use of the word strategic should set off your alarms. In business it rarely refers to strategy anymore; it has become a code word that means "losing lots of money."

- We failed to correctly account for costs. When we were bidding projects or planning new products, we used only unburdened costs in our calculations. We accounted for the raw cost of goods and the actual wages associated with the labor, but we made no allowance for the overhead that goes with all the costs: raw goods were handled and stored; people sat on chairs at desks on floor space we leased. Our team was supported by receptionists and bookkeepers and other personnel whose costs we failed to associate with any specific project.

- We lost a little on each unit and tried to make it up in volume. By promoting the extra value to the consumer, we were succeeding at getting more customers to choose our top-end product instead of a less-expensive configuration. We were excited to see this happening but confused as to why we were not making even more money. When we were finally forced to sit down and do a real cost analysis, we found out that this product had more than twice the raw costs we thought and that we were losing money every time we sold it. And we were up-selling more and more users to this money-losing configuration every day.

At the heart of all these bad decisions was a fear of losing business or missing opportunities. What I failed to understand back then was that losing unprofitable business is a very good thing. Why would anyone want unprofitable business? Something that is not profitable is not an opportunity; it is a waste of time.

Everything You Do Should Be Profitable

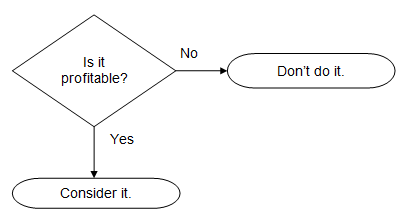

Impending doom is a wonderful motivator. I had signed personal guarantees; if the business failed I would go down with it. Facing, at last, the prospect of personal ruin, I became obsessed with profitability. As an organization we attacked costs, promoted sales, and developed a powerful new decision-making system to help turn our business around:

As you can see, the new system did not add too much complexity to our decision-making process. It was relatively simple to implement. It did, however, make a big difference in our business.

In one of the first applications of the new decision-making system, we evaluated the business prospects of a new piece of software we had developed. We were confident that there was a large market for it but realized that it was outside our core audience. We did not have access to the right customers nor the resources to establish ourselves in this new area.

We sold the software to another company that was already established in the new market. The deal was profitable for us and allowed us to stay focused on our primary product line. I was very proud of our newfound responsibility in finding a profitable alternative to an unprofitable foray into a new market.

A few weeks after the deal closed the buyer asked for some extra work from our programmer. Feeling good about the fact that we had made a profit on the deal I prepared an estimate based on our cost for the programmer's time. "It's still profitable," I told myself.

Then my internal alarm sounded. The software sale was a done deal. Contracting out the programmer's time was a new deal, and I was planning to do it at cost. In fact it would not be at cost, it would be at a loss, since I was not accounting for overhead or lost time on our own projects.

I doubled the quote for the programmer's time to ensure I covered all our overhead expenses. Then I doubled it again to make sure it was profitable. And then I rounded it up to a nice, even sum.

I was sure that the buyer, who knew the value of a programmer's time, would balk at the inflated quote. But the buyer happily agreed because he was wiser than I was. The buyer expected me to make a profit when selling him services just as he expected me to make a profit when I sold him the software. He, in turn, expected to make a profit on the programmer's work when he took the product to market. Why else would either of us be in business if not to make a profit?

Stand Firm for Profit

Few customers have the temerity to ask you to take their business at a loss. Most will at least give lip service to your need to make a profit. They would just like to define your profit as a positive number approximating zero.

Like an endless stream of new car buyers waving "actual dealer invoices," your customers will constantly attack your profit margin. They don't wish you ill, they just need a little discount, and surely, in your big fat profit margin you have room to move just a little bit, right?

Don't do it! Stand firm! You do not really want to join the car dealers in a world where every sale is a battle and customers worry that they got a worse deal than their neighbor, do you?

If your price is too high or your margin too fat, you will find out soon enough: you won't have any customers at all. If that is not the case and your price and profit are right, then you do not need to bend for any single customer. Making an exception to avoid losing one deal or one customer is like making one hole in a dam. It won't be long before your leak is a flood.

Put Profit First

Profit is the first mission of every business. It protects and enables all the others. Goals may inspire your business and cash may keep it alive, but if your business is not pursuing a profit it is not a business, it is a hobby. Or a money pit. Or a massive black hole that will absorb your time, effort, hopes, dreams, and financial future. Take your pick.

When we learned the importance of profit in my business, we not only changed our decision-making process, we changed our spreadsheets. We hardwired a minimum profit margin into every financial decision. Our budgets have a fixed-percentage profit allocated before any other costs; profit is the only unassailable line item.

In my personal finances over the years, poor planning or unexpected expenses have caused me at one time or another to be late paying a bill. I have never missed an income tax payment, though, because it is withdrawn from my paycheck before I receive it. Having the taxes set aside before the paycheck is drafted ensures their priority.

While we were learning the discipline of putting profit first, we used this same technique. We physically set aside our minimum profit margin from each day's sales out of that day's cash receipts. By immediately taking the profit out of our working cash, we protected it against erosion from unexpected expenses. We were forced to track sales and costs more closely and to be more careful in our planning because the funds allocated to profit were taken out of the equation. In the course of each year, our overall profit still varied but rarely below that set-aside minimum.

Profit can be defined as what is left of your revenue after you have covered your expenses. That is a risky definition for something that protects your business future and enables you to accomplish your business purposes. Define profit as the priority, not the leftovers. After all, profit is why you are in business.